These childhood experiences inspired some of the world's best video games.

One of the great things about video games is how they let us feed our desire for adventure and exploration. That’s something that adults don’t get to do so much in our daily lives. But you know who does? Kids.

With their fervid imaginations, kids are often out and about on incredible journeys that blend fantasy and reality to create something truly special. These adventures can become indelible memories that shape them for life.

Some of the most notable video games of all time were inspired by these childhood experiences. Let’s explore a few and learn about what memories designers treasure from their youth and draw on for their work.

The Legend Of Zelda

Perhaps the most famous game designer in the world, Shigeru Miyamoto is responsible for most of Nintendo’s most iconic franchises. As a child, he lived in rural Sonobe outside of Kyoto and spent his time exploring the natural world.

One of his most formative experiences came when he came across a cave in the side of a mountain. It took him several days to muster up the courage to venture inside, but the experience stayed with him into adulthood. After finding success with Donkey Kong and its sequels, Miyamoto was tasked with creating a new sort of game for Nintendo’s home console.

That game was The Legend Of Zelda, where a young man explores a massive (for the time) world without any signposts or guides. It was a direct outgrowth of Miyamoto’s childhood wanderings, attempting to recapture the feeling of stumbling upon something totally unexpected.

In addition, the sliding doors of his parents’ house, which would move to reveal new rooms and change the shape of existing ones, inspired Zelda’s lock and key dungeons where Link flipped switches and gained new tools before fighting a boss.

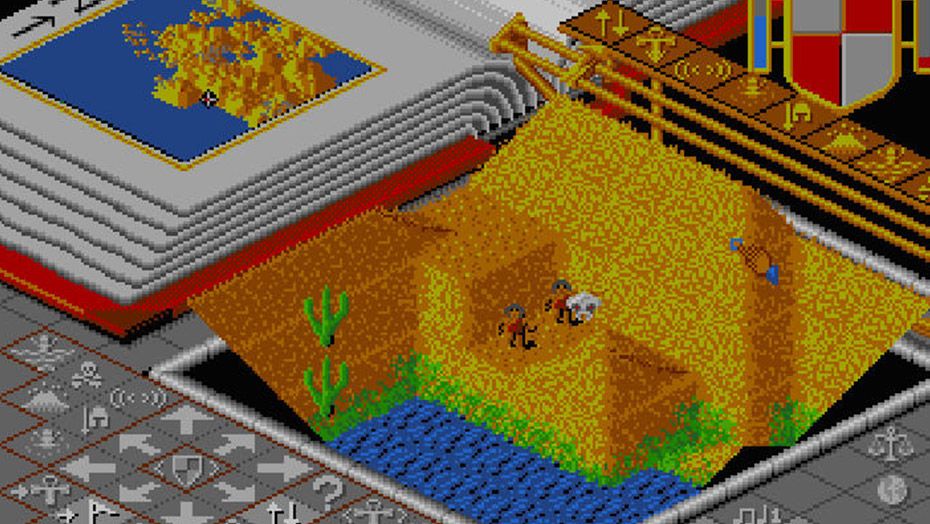

Populous

Growing up in Guildford, young Peter Molyneux once stumbled upon a bustling anthill. Following the instinct that most young boys share, he picked up a stick and disturbed the hill, causing the social insects to panic and swarm as their world crumbled around them. He then ran home and bought some sugar, sprinkling it down into the hill and watching the ants organize to bring it inside and rebuild.

As a boy, Peter’s dyslexia prevented him from doing well in school, and his undersized physique did the same on the athletic field. But when his boarding school got a Commodore PET, the young man became focused on creating a version of Space Invaders for the computer, and a game programmer was born. He started out building productivity software, but in 1987 incorporated Bullfrog Productions to make games for the cutting-edge Commodore Amiga.

Bullfrog’s breakthrough game was 1989’s Populous, the first in what would become the genre of “god games.” It put the player in a bird’s eye view over a small village of primitive people and tasked them with helping them thrive. You can’t communicate with them directly, only shape their environment with earth, wind, and water to guide them. It’s a digital version of little Peter’s experiments with the anthill.

Pokemon

Satoshi Taijiri grew up in suburban Machida, outside of Tokyo. As a child, he wanted to be an entomologist and started building a collection of insect specimens that he captured. He was so into the hobby that his classmates nicknamed him “Mr. Bug.”

As he entered his teens, though, Taijiri lost interest in the insect kingdom and instead gravitated to video games, buying a Famicom (the Japanese Nintendo console) and completely disassembling it to figure out how it worked. He studied electronics in college, and, in 1989, founded the development studio Game Freak.

The next year, after watching a demonstration of the Game Boy’s link cable, which allowed two portable consoles to communicate, Taijiri returned to his childhood of catching and trading bugs to come up with the core idea for Pokemon. It took the new company six years to finish the first game, nearly bankrupting it, but it was a near-instant success that spawned a massive franchise.

The experience of slowly walking through tall grass hoping to uncover a new insect is deftly translated into pixels, making the game a fantastical recreation of its creator’s childhood obsession.

Dark Souls

Hidetaka Miyazaki was raised in poverty in the Japanese city of Shizuoka and, because his parents couldn’t afford toys or media, spent much of his time borrowing books from the local library. For some reason, they had a sizable English fantasy section, which young Miyazaki dove into despite his rudimentary knowledge of the language. He filled in the gaps of his understanding with his imagination, threading stories together from the illustrations and what text he could parse.

After going to college to study social science, Miyazaki took a job with software company Oracle. At 29, he abandoned his career to take an entry-level coding job at FromSoftware, an iconoclastic Tokyo-based developer. His big break came when he was tapped to take over a struggling action-adventure called Demon’s Souls.

A franchise beloved by the hardest of the hardcore, the Souls games drop the player into a forbidding fantasy world where death lurks around every corner and they must think on their feet and work to survive. They’re lauded for their environmental storytelling, which dispenses with exposition and forces gamers to learn by observation and close attention to understand their plots. That style of narrative is directly descended from Miyazaki’s childhood afternoons in the library, where he learned the satisfaction of piecing together a story out of half-understood fragments.